How hot does

it feel outside?

It’s more than temperature

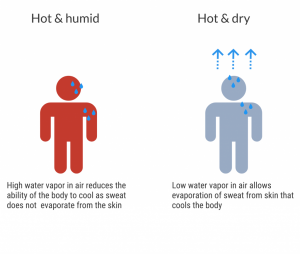

The human body works best within a narrow temperature range of around 36˚C. Once the ambient temperature starts to exceed this the body’s response to reduce heat includes sweating, where the evaporation of the sweat from the surface of the skin to help cool the body1. The importance of evaporative cooling by sweating to reduce body temperature means that there is the need to consider more than the ambient temperature in evaluating potential heat stress2. This is particularly the case in Darwin during the build-up and wet seasons, where heat stress is influenced by the amount of moisture in the air.

Apparent temperature

The Bureau of Meteorology (BoM) reports on apparent temperature (AT) that represents the perception of ambient temperature adjusted for relative humidity and wind speed3. The apparent temperature is what it ‘feels like’ versus what it says in the thermometer, called ambient temperature. By considering wind and humidity, the apparent temperature indicates what the level of discomfort a person would feel considering how much heat the wind would remove or if humidity levels were high enough that sweat could not evaporate off skin to help cool the body.

Dew point temperature

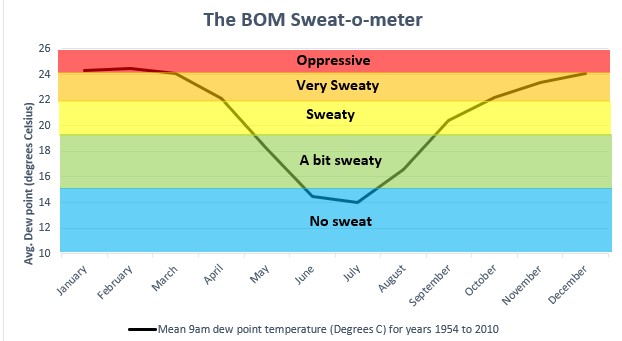

In hot climates, like Darwin, dew point temperature might provide a better indication of potential heat stress than apparent temperature, which uses relative humidity. Dew point temperature reflects the temperature at which condensation will start to occur, which measures the amount of moisture in the air4. A higher dew point temperature will indicate there is more moisture in the air, which reduces the ability of sweat to evaporate to help the body cool. The BoM sweat-o-meter indicates how people might feel for different dew point temperatures. In Darwin during the build-up and wet seasons the warm is saturated with moisture, which means that people will often find the conditions oppressive and uncomfortable.

Image: © Copyright Commonwealth of Australia 2012, Bureau of Meteorology References

References

- Belval, L. N.; Morrissey, M. C., Physiological Response to Heat Stress. In Exertional Heat Illness: A Clinical and Evidence-Based Guide, Adams, W. M.; Jardine, J. F., Eds. Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2020; pp 17-27.

- Oppermann, E.; Brearley, M.; Law, L.; Smith, J. A.; Clough, A.; Zander, K., Heat, health, and humidity in Australia’s monsoon tropics: a critical review of the problematization of ‘heat’ in a changing climate. WIREs Climate Change 2017, 8, (4), e468.

- Bureau of Meteorology Apparent (‘feels like’) temperature.http://media.bom.gov.au/social/blog/1153/apparent-feels-like-temperature/ (Accessed May 2020)

- Bureau of Meteorology Feeling hot and bothered? It’s not the humidity, it’s the dew point. http://media.bom.gov.au/social/blog/1324/feeling-hot-and-bothered-its-not-the-humidity-its-the-dew-point/ (Accessed May 2020)

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

Your Tropical City acknowledge the Larrakia people as the Traditional Owners of the Darwin region and pay our respects to Larrakia elders past and present. We are committed to a positive future for the Aboriginal community.

564 Vanderlin Drive,

Berrimah NT 0828

(08) 8944 8436

hello@yourtropicalcity.com.au

PARTNER

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

Your Tropical City acknowledge the Larrakia people as the Traditional Owners of the Darwin region and pay our respects to Larrakia elders past and present. We are committed to a positive future for the Aboriginal community.

CONTACT

564 Vanderlin Drive,

Berrimah NT 0828

(08) 8944 8436

hello@yourtropicalcity.com.au

PARTNER